Transplant Cancer Risk Calculator

Your Estimated Cancer Risk Profile

Overall Relative Risk

compared to general population

Skin Cancer Risk

for squamous cell carcinoma

Risk Factors Influence

Important Notes

- Risk increases significantly in the first few years post-transplant

- Higher immunosuppression intensities correlate with increased cancer risk

- EBV positivity raises risk for PTLD and other malignancies

- Regular screening and sun protection are critical

When a transplanted organ is recognized as foreign, organ rejection is the immune system’s attack on the donor tissue, leading to inflammation and potential loss of graft function can occur. To stop that attack, doctors prescribe immunosuppressive therapy a cocktail of drugs that dampen the immune response so the new organ can survive. While life‑saving, these medicines also dim the body’s natural cancer‑fighting surveillance, which is why transplant recipients face a higher cancer risk the probability of developing malignant tumors compared with the general population. This article unpacks the biology behind that link, highlights the cancers that show up most often, and offers practical steps to keep both graft and health in check.

How Organ Rejection Works

A healthy immune system constantly patrols for anything that looks out of place. When a donor organ arrives, it carries proteins called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) that differ from the recipient’s own. Transplant recipient the person who has received a donor organ’s immune cells-especially T‑cells-recognize those mismatched HLAs as threats and launch an attack. The process can be acute (within weeks) or chronic (over years). Acute rejection often shows up as fever, pain, or organ dysfunction, while chronic rejection slowly scars the graft, leading to eventual failure.

Why Immunosuppression Raises Cancer Risk

The same drugs that calm the rejection response also suppress the immune system the body’s network of cells that identify and destroy abnormal cells and pathogens. Under normal circumstances, immune cells spot and eliminate cells that have acquired DNA damage-an early step in cancer formation. When that surveillance is blunted, several pathways open up:

- DNA repair mechanisms become less efficient, allowing mutations to accumulate.

- Oncogenic viruses such as Epstein‑Barr virus (EBV) or human papillomavirus (HPV) can reactivate or establish persistent infections.

- Growth‑factor signaling is altered by drugs like azathioprine, which can directly promote cell proliferation.

In short, the trade‑off for graft survival is a higher chance that rogue cells slip through the cracks.

Common Cancers After Transplant

Not all cancers rise at the same rate. Large registry studies (e.g., the European transplant cancer registry, 2023) show a pattern:

- Skin cancers - especially squamous cell carcinoma, which can be up to 100‑times more common than in the general population.

- Post‑transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) - a spectrum of B‑cell proliferations driven largely by EBV; incidence peaks within the first two years after transplant.

- Kidney and bladder cancers - often linked to chronic immunosuppression and the underlying renal disease.

- Liver and lung cancers - higher in recipients with viral hepatitis or a history of smoking.

These cancers tend to appear earlier and progress faster, making vigilance essential.

The Role of Oncogenic Viruses and PTLD

Viruses that can insert their genetic material into host cells are a major hidden danger. Oncogenic viruses viruses like EBV, HPV, and hepatitis B/C that can trigger malignant transformation exploit the weakened immune environment. EBV, for example, can transform B‑cells into proliferative lesions that evolve into PTLD. The risk correlates with the intensity of immunosuppression: higher drug levels, especially of calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, cyclosporine), raise PTLD odds three‑fold.

Cancer Incidence: Transplant Recipients vs. General Population

| Cancer Type | Transplant Recipients | General Population | Relative Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Squamous cell skin cancer | 27.4 | 0.31 | ≈88× |

| Post‑transplant lymphoproliferative disorder | 1.2 | 0.02 | ≈60× |

| Kidney cancer | 3.1 | 0.5 | ≈6× |

| Lung cancer | 4.5 | 2.8 | ≈1.6× |

| Melanoma | 2.0 | 0.7 | ≈2.9× |

The numbers make it clear: skin cancers dominate, but the overall cancer burden is roughly double that of non‑recipients.

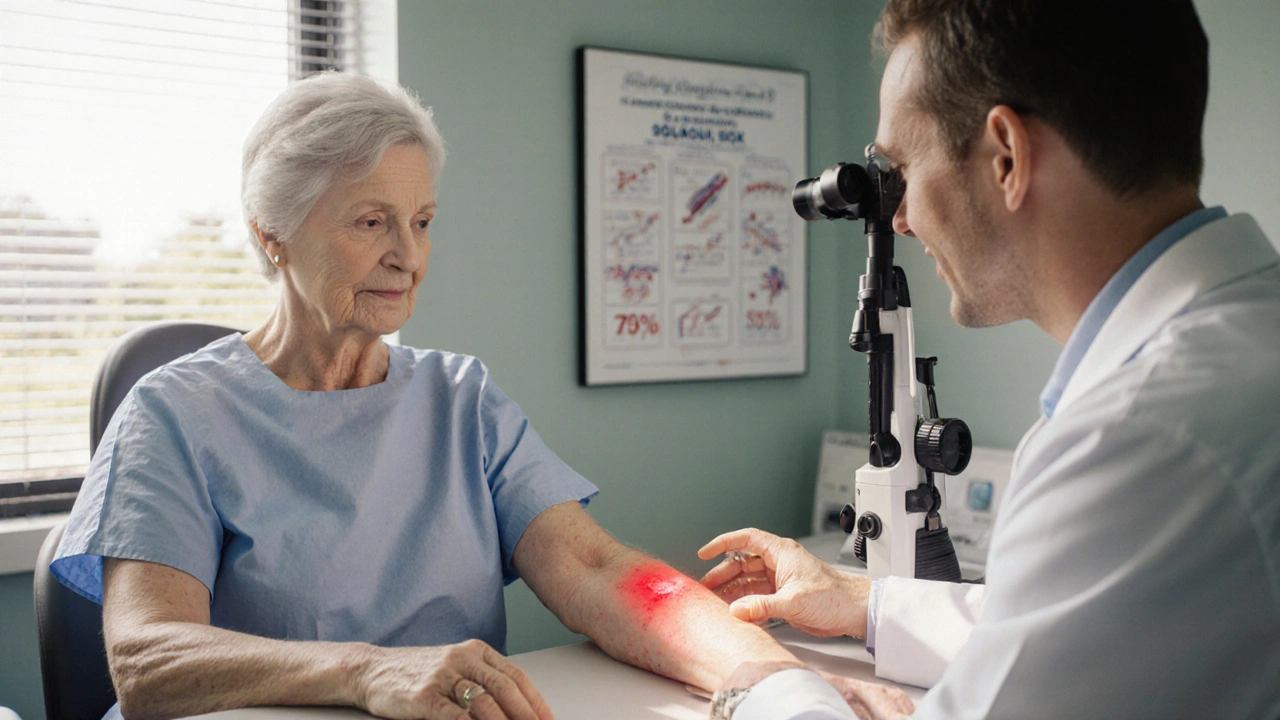

Prevention and Screening Strategies

Because risk can’t be eliminated, clinicians focus on early detection and lifestyle tweaks. Here’s a practical checklist for patients and providers:

- Skin exams: Full‑body check every 3-6months by a dermatologist; self‑exams weekly.

- Viral monitoring: Quantitative EBV PCR every month for the first year; HPV vaccination before transplantation when possible.

- Imaging: Annual low‑dose CT for lung‑cancer screening in smokers; ultrasound of the transplanted organ to catch early neoplasia.

- Laboratory tests: Periodic liver function tests, serum creatinine, and tumor markers (e.g., AFP for liver).

- Lifestyle: Sun protection (SPF30+, protective clothing), smoking cessation, and a diet rich in antioxidants.

These measures have been shown in prospective cohorts (e.g., US transplant registry 2022) to reduce mortality from post‑transplant cancers by about 15%.

Balancing Immunosuppression to Lower Cancer Risk

Tailoring drug regimens is a fine art. Strategies include:

- Minimization protocols: Lowering calcineurin inhibitor doses after the first year when graft function is stable.

- Switching to mTOR inhibitors (e.g., sirolimus, everolimus): These agents have antiproliferative properties and are associated with a 30‑40% drop in skin‑cancer incidence.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring: Keeping trough levels within the narrow therapeutic window to avoid over‑suppression.

- Individual risk assessment: Factoring age, prior cancers, and viral serostatus before choosing a regimen.

Regular multidisciplinary meetings-transplant surgeon, nephrologist (or hepatologist), oncologist, and pharmacist-ensure that the plan evolves as the patient ages.

Key Takeaways

- Immunosuppressive drugs essential for preventing organ rejection also blunt the immune system’s cancer surveillance.

- Skin cancers and PTLD are the most common post‑transplant malignancies; they arise earlier and progress faster.

- Relative risk of cancer in transplant recipients can be 2‑100× higher, depending on the type.

- Active screening (skin checks, viral monitoring, imaging) and lifestyle measures dramatically improve outcomes.

- Adjusting immunosuppression-especially using mTOR inhibitors-helps lower cancer incidence without sacrificing graft survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do transplant patients get skin cancer more often?

The skin is directly exposed to UV radiation, which creates DNA damage. Immunosuppressive drugs reduce the skin’s ability to repair that damage and to eliminate mutated cells, so cancers like squamous cell carcinoma appear far more frequently.

What is post‑transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) and how is it treated?

PTLD is a spectrum of abnormal B‑cell growth driven mainly by EBV infection in the setting of heavy immunosuppression. First‑line treatment is to reduce or switch immunosuppressive agents; rituximab (anti‑CD20) and chemotherapy are added for aggressive disease.

Can I receive a COVID‑19 vaccine after a transplant?

Yes. Vaccination is strongly recommended, though the antibody response may be lower. Some centers advise a third booster dose and checking serology to gauge protection.

Do lifestyle changes really lower cancer risk after transplant?

Lifestyle measures-especially diligent sun protection, quitting smoking, and maintaining a healthy weight-have been linked to a measurable drop in post‑transplant skin cancers and lung cancers, according to cohort studies published in 2022‑2024.

How often should I see my transplant doctor for cancer screening?

Most guidelines suggest a comprehensive review every 6months during the first two years, then annually once graft function is stable. Specific screening intervals (e.g., dermatology visits every 3-6months) depend on individual risk factors.

Andrew J. Zak

October 7 2025Immunosuppression definitely raises cancer risk.